The Kanabi Killings

Most international coverage of Sudan’s civil war – including our own – has focused on the horrific atrocities perpetrated by the RSF against civilians. Ethnic cleansing and anti-Black racism are well-known features of violence against civilians in western Sudan. However much less attention has been directed to similar anti-Black violence perpetrated by SAF in eastern Sudan.

Using a combination of confidential sources, on-the-ground reporting, and open source evidence, we have confirmed a systematic pattern of mass killing and displacement perpetrated by the Sudanese Armed Forces and allied militias against Kanabi farming communities, known as kambos, in Jazira and Sinnar states.

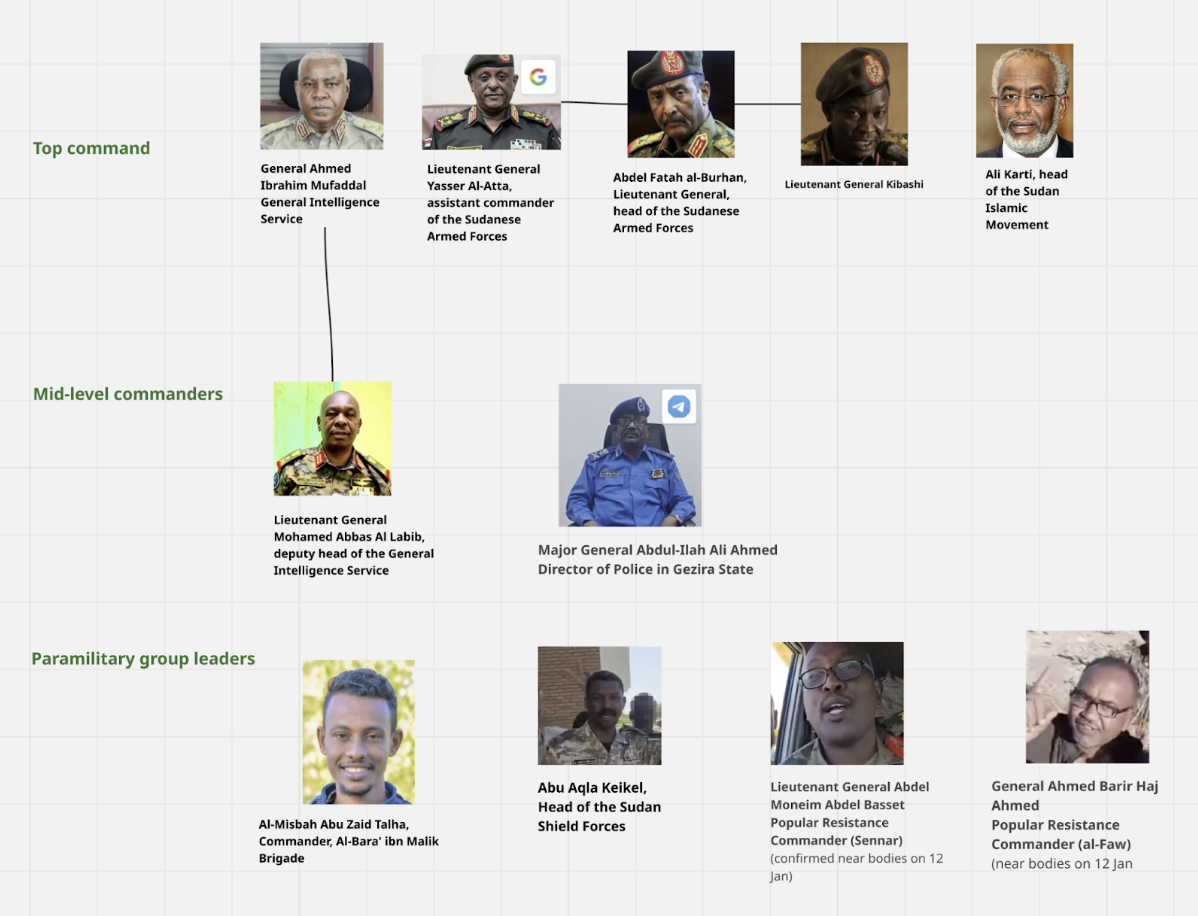

These killings were conducted with the knowledge and support of high-ranking officers in the Sudanese Armed Forces, General Intelligence Service, and allied militias including the Sudan Shield Forces and al-Baraa bin Malik Brigades.

To reach these findings, we assembled three main groupings of evidence:

Accessing information inside Sudan is incredibly difficult. There is an ongoing war, forced displacement, and mass exile. Journalists and human rights activists are systematically targeted, harassed, and arrested. Communication blackouts and disinformation campaigns further fracture an already fraught online landscape. This leaves marginalized groups with even less opportunity to shape narratives.

In light of these challenges, we prioritized building relationships with sources when developing our methodology, investigative priorities, and open-source search parameters. This document describes our approach and how we attempted to account for the challenges and limitations associated with covering Sudan.

We encourage civil society organizations and organizations working on justice to reach out to us to learn more about our methodology and for access to our databases (excluding information regarding confidential sources for their protection).

We conducted dozens of interviews with survivors, witnesses, and whistleblowers in Sudan– including 8 in-person with survivors and 5 with whistleblowers. Though difficult to obtain given mass calamity, these interviews were a vital lifeline to the truth on the ground in a landscape of “information warfare.”

We identified sources primarily through our network of Sudanese reporters and conducted interviews with survivors, witnesses, and whistleblowers in three ways: Lighthouse Reports conducted phone interviews; Sudanese journalists conducted ground interviews; an international journalist interviewed survivors and witnesses on camera.

All of the survivors and witnesses we interviewed were from a non-Arab background. Most identified as part of the Kanabi community, though some were unaware of the term. All of the whistleblowers were active members of the SAF forces or their allied groups, and all were directly involved in fighting in Jazira State.

In order to protect the identity of our sources, we cannot publicly say where the interviews took place or how we ensured the safety of our sources.

Interviewees who agreed to be filmed had their faces hidden and did not state their names on tape. The material was uploaded on the day of the interviews and deleted from hard drives to avoid crossing borders with sensitive material.

We collected references to attacks on kambos from interviews with confidential sources and cross-referenced those locations with open-source information to produce a database of 57 confirmed and 87 reported, partially confirmed kambos which were attacked between October 2024 and May 2025.

We prioritized kambos, whose residents are historically all Kanabi, and deprioritized violence against Kanabi people in urban areas because of the difficulty in confirming victims’ ethnicity in multi-ethnic areas. (See “Police Bridge Massacres” and “Challenges and Limitations” below.)

For each village, we confirmed: (a) the geographic coordinates of the village, (b) the presence of a kambo in that location, and (c) corroborating evidence of mass violence in the time and place described, with a one-week margin to allow for minor discrepancies in witnesses’ recollection. When we could not find the exact location of the kambo, we relied on the nearest town.

Due to the lack of reliable geospatial data in Sudan, inconsistent naming conventions for villages, and village names that are generic or repeated across the state, geolocating attacks on villages required multi-layered corroboration.

Our primary challenge was that although an interview subject could describe an attack on a village, we couldn’t find its location. Most kambos do not have an online presence. But once we had the location of a village, we could access tons of information to corroborate the interview data. We could determine whether SAF was present or if burn scars appeared on the dates an arson was described. Therefore, geolocating villages was necessary and constituted the bulk of our verification work.

To find a village, we started– when possible– with contextual information from interview sources, such as “My village is 20 kilometers east of X town.” We could also find village names by searching through individual user-generated tags on multiple web mapping platforms, such as Google Maps, Wikimapia, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, and maps by the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team. A village might not be listed, but a public building, such as a mosque, school, playground, or farm, could contain the village name in its tag. We could then use this tag as a reference point to compare with other data points.

When that wasn’t possible, we pivoted from other information from the interviews. For example, an attack date and description of uniforms could mean that we search for a specific troop presence, which could lead us to a more precise location. That location could then be another starting point for pivoting or corroboration.

Corroborating data included:

Each verified village’s geolocation includes a precision rating demonstrating its accuracy and a hyperlinked source for the location. This includes cases in which we could only geolocate a village to the nearest major town or city because we could not confidently determine its precise location.

We primarily relied on witness testimony to determine the date of an attack. When the exact date was unclear, we estimated it based on the presence of SAF in the area and noted this in the database.

We considered an attack “verified” if it met a three-source standard: our interviews, and a combination of secondary sources that confirmed the attack was carried out by SAF or SAF-aligned forces in that location at that time. We considered kambo attacks “reported” if they appeared in our interviews and/or one additional secondary source as attacked by SAF but could not definitively meet the three-source threshold.

Our database is organized by village rather than by attack. Counting by village allowed us to observe the lifecycle of an attack, log multiple attacks on a single location, and mitigate the risk of duplicate counts if interviewees from a single village experienced multiple attacks or have date discrepancies.

Each kambo verified as attacked includes an English and Sudanese Arabic name, coordinates, location precision, attack dates, the number and type of sources, a description, the militia group named, visual or open-source links from ground reporting or our collection, and thematic tags (see “Archiving and Organizing Visual Evidence”).

What we searched for

While ground reporters provided and obtained images of particular locations, the bulk of our nearly 600 images–mostly videos–were collected from social media and local news in an iterative process that identified and incorporated new search terms and investigative priorities through repeated searches.

Keeping in mind standard best journalistic practices and the Berkeley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigations, we set out to collect, archive, source, verify, and analyze images of the following, occurring in Sinnar or Jazira state after 1 October 2024:

The priority locations and date range were decided upon based on the information gathered during the interviews. Qualifying violent incidents include beating, killing, extrajudicial detention, torture, and sexual or gender-based violence. Our scope was limited to violence by ground forces as airstrikes were excluded due to difficulty of evaluating targeting and proportionality without extensive systematic analysis.

“Civilian” refers to an individual of any age or gender wearing civilian clothing, excluding non-standard issue khaki or camouflage pants, which are commonly worn by irregular combatants. This may result in false positives on preliminary review, due to the high number of armed actors who don’t wear uniforms during combat as well as the possibility of combatants wearing civilian clothes while attempting to flee.

“SAF or SAF-allied forces” refers to any official or semi-official ground forces participating in armed conflict against the RSF in coordination with the Sudanese Armed Forces. This may include government agencies outside the authority of the Ministry of Defense (for example, police or General Intelligence Service) as well as paramilitary groups like the Popular Resistance Forces or Sudan Shield Forces. We limited our search to either combatants wearing uniforms or groups of visibly armed individuals wearing a mix of uniforms and plainclothes. RSF uniforms and groups of all-plainclothes combatants without identifying insignia like patches or armbands were excluded.

Although Sudanese team members identified local slurs and racialized insults, in many cases, racist and xenophobic language was observed but the specific ethnicity of the victims was difficult to ascertain without further context.

Where we searched

There is limited available data on social media usage in Sudan. Therefore we relied on guidance from Sudanese team members and partners to select Facebook, Telegram, TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), and WhatsApp. We found the majority of our evidence on Facebook and Telegram, with some contributions from X, and found searching in Arabic to be more effective.

Using broad search terms like “Sudan,” “Sinnar,” “kambo,” “Sudanese Armed Forces,” or “Rapid Support Forces,” we identified popular and active channels posting content related to local news in central Sudan. For each channel identified, we also reviewed similar channels suggested by the platform. Due to limitations in Telegram’s default user interface, we supplemented our initial searches in Telegram with third party search engines and channel directories such as Telemetrio and TGstat. TikTok has similarly poor search functionality, so we first trained our research accounts’ algorithms by searching for usernames known to be associated with relevant videos (see “What we searched for,” below).

The majority of channels found were determined to be aggregators that recirculated similar content. Over time, we pruned the list of channels down to only the most productive: the channels that posted mostly original content, high-definition images, and/or posted popular images first. Preference was given to channels belonging to front-line parties to the conflict, such as individual combatants, military units, or embedded war correspondents posting their own original content.

How we searched

Following the investigative priorities derived from witness interviews, we developed a standardized list of search terms such as locations, names of armed groups, or names of significant individuals. We searched for these terms on each platform in rotation in three phases: first, we searched for terms across the entire platform to include results from all channels. This phase also served to further identify and prioritize new relevant channels.

Second, we searched for a refined list of search terms within each high-priority channel. By this stage, the more targeted search results often revealed hashtags, slogans, local slang, and other unique phrases that were added to the list of search terms. With the help of Sudanese colleagues, we identified a subset of higher priority keywords including but not limited to location names, names of local factions, racial slurs, and local euphemisms. We also updated the hashtags and locations as our investigative priorities evolved.

In our third and final stage, after we had chosen a narrower time frame in mid-January 2025, we returned to the highest-priority channels, those determined to belong to combatants and embedded war correspondents. We reviewed all media in chronological order ranging from the start of the campaign to re-take Wad Madani on 8 January, through the recapture of Wad Madani on 11 January, until 31 January, anticipating that some evidence may be posted after a delay, especially where internet or mobile data access is limited. In many cases, these accounts posted unique or original content with vague captions or no captions at all, which had completely evaded our previous searches.

Visual evidence shared with us by partners

After we narrowed our focus to Jazira state during mid-January, colleagues at the Center for Information Resilience graciously shared their data corresponding to our geographic area of interest and time frame, including geolocation notes and degree of verification. (We treated their geolocations as leads to be confirmed independently.)

Archiving and organising visual evidence

For data preservation, we primarily relied on Bellingcat’s open source auto-archiver program, which takes a spreadsheet of URLs and extracts several types of data:

Our digital archive is searchable by location, date, and thematic tag. All content in the archive, particularly allegations in tags and captions, is considered unverified until further review and corroboration.

Locations are based on the presumed location stated or implied by the caption, visual cues, or recommendations by Sudanese team members. Dates refer to the date of the social media post. No additional geolocation or chronolocation is done at the archival stage.

Tags refer to apparent, presumed, or implied events, including events off-screen or alleged in captions. These tags describe unverified reports and are not factual claims by Lighthouse Reports or its partners.

See “Incident types” below for descriptions and examples of some of the incident tags in use.

Extracted data was stored in Google Drive with enterprise-level security (end-to-end encryption) and access controls defined by Drive permissions for investigations team and partners only. Investigative team communication took place via encrypted chat and video calls (Signal).

Verification

Due to resource and time constraints, we could not verify each piece of visual evidence collected. Based on editorial priorities, we prioritized materials involving locations and armed groups named by confidential sources, which had a higher possibility of verification.

This also means, however, that images that did not have context clues regarding location, as well as locations not mentioned by sources, did not receive the same level of attention.

Sourcing

For many images, the original source could not be definitively identified, but we attempted to find the highest resolution and earliest available copy. Earlier copies were less likely to have incorrect captions and helped narrow down the possible window in which a given image was recorded.

Geolocation and chronolocation

We followed a standard procedure for geolocation which involved:

To analyze when an event was filmed (“chronolocation”), we used:

Verifying context

We verified the context of visual evidence through multiple methods:

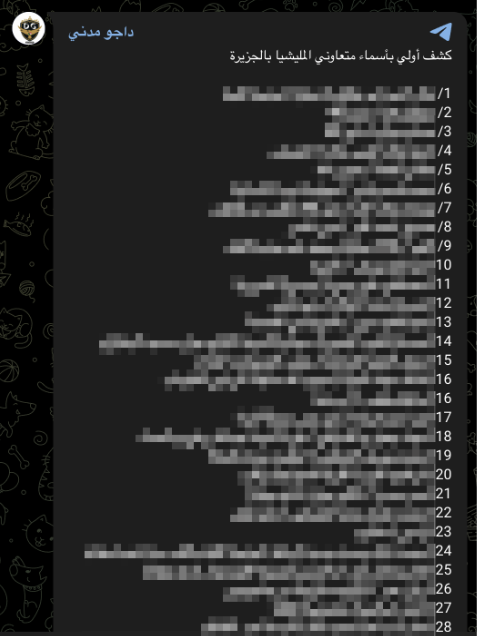

Incitement

We archived 28 speeches by public officials, voice notes, and social media posts condemning all civilian residents of RSF-controlled areas as RSF collaborators or spies. Facebook groups and Telegram posts include the names of alleged RSF collaborators and encourage vigilante violence against them. Some of these accusations characterized an entire group as collaborators based on their ethnicity.

Arrest and Detention

We archived 185 videos that appear to show uniformed soldiers arresting groups of people, usually but not always young men, wearing civilian clothing. The detainees are frequently tied up or blindfolded, and often transported in pickup trucks. Sometimes they are bloody or there is onscreen violence.

It is common for either the onscreen soldiers or the image’s caption to have to use racist language against perceived South Sudanese or Western Sudanese. In some cases, they directly or indirectly refer to Kanabi people specifically, but much of the time the slurs or insults used are non-specific.

Most videos of arrests are filmed outdoors and do not provide information about what happened to the arrestees or where they were taken. Instead, hashtags and comments often refer vaguely to violence.

A handful of videos depicted prisoners wearing civilian clothes in detention centers. In one case, we were able to geolocate two detention centers and confirmed with sources that the detainees who were filmed there were transported from one location in Dinder, Sinnar state, to the other in Hawata, in the neighboring state of Gedaref. Unfortunately, such examples are rare.

According to reports by Sudanese human rights groups, the SAF and allied forces have carried out arbitrary arrests and torture in detention facilities, including in Sinja (Sennar), with arrests being made along tribal and gender lines.

Sources interviewed for our investigation have told us that Kanabi residents were arrested based on their ethnicity, transported to Sinja or another town for detention, held in unsanitary conditions, and sometimes disappeared or died while in detention.

Torture and gender-based or sexual violence (GBSV)

We archived 55 images of possible torture and of possible GBSV. While a handful recorded the act of torture, most relevant images that we found show the dead bodies of young men, often in uniform, whose injuries appear intentionally inflicted and cannot be easily explained by combat. Indications of possible torture/GBSV include but are not limited to restraints and blindfolds; isolated injuries, particularly to the face, genital area, or buttocks; and absence of weapons, gunshot wounds, fire damage, or other indications of possible combat, shelling, or airstrikes. Because we limited our scope to violence against civilians, we did not archive images involving possible victims wearing uniforms.

However, without more context or a forensic analysis, it is difficult to determine causes of specific injuries with certainty, and therefore difficult to determine which images depict torture and GBSV versus post-mortem mutilation or combat injuries. Due to the risk of false positives, we have chosen to limit our conclusions on these images to “possible torture” unless there is additional information to support a stronger conclusion.

Conversely, there may be false negatives in some cases of severely burned bodies. Burns occur frequently during combat and air strikes, so unless a confidential source, caption, or other context clue suggests that a person was deliberately set on fire while still alive, burned bodies are not tagged with “torture.”

Killings

Posts with this tag also include implied killings to make it easier to group videos of the same incident.

If a video features dead bodies but does not show the moment or manner of death, it would nonetheless be tagged “killing.” Videos of armed guards with unarmed prisoners in which the camera turns away immediately prior to the sound of gunfire are also tagged as “killing.”

Videos depicting one or more detainees with a caption implying subsequent killing were tagged with both “detention” and “killing.” In these cases, the description field explains that the video shows a detention and the caption is the only (unverified) source for the murder allegation. If the murder allegation cannot be proven, the alleged detention can still be verified or disproven separately.

It is crucial to remember that these videos are unverified until proven otherwise. Also, images may be tagged as both detention and killing, so caution should be exercised when attempting to aggregate total numbers.

Burning

We used the term “burning” to flag villages showing active fires or smoke, as well as those with burn scars or evidence of fire, such as burnt cars, homes, or bodies. This tag also includes some screenshots of burn scars from satellite imagery and reports of villages being set ablaze.

We avoided the term “arson” because without additional analysis, it would be difficult to exclude the possibility of wildfires, controlled agricultural burns, airstrike-related burns, though burning was often mentioned in interviews as part of the attack pattern by the SAF and allied groups.

Additional tags

We did not intentionally search for air strikes, so the “airstrike” tag is intended as a way of filtering out images of burning buildings later determined to be outside the scope of our investigation.

Priority categorization flagged high interest videos for second level review based on how many of the following criteria were met:

The sequence of events on the outskirts of Wad Madani, as featured in our publication, demonstrates most of the above categories of abuse. These images and posts corroborate whistleblower descriptions of killings at Bika, Kariba, and Police Bridge, and descriptions of mass graves and bodies deposited in canals.

The screenshots below are only a small portion of the images recovered from Police Bridge. We’ve chosen to limit the amount of graphic materials we include in this methodology, but all videos from our analysis are available in our archive. Please reach out to us for access.

11 January: SAF coalition recaptures Madani as social media posts encourage vigilantism

On 11 January, two different fronts of pro-SAF forces converge on Wad Madani: one from the east via Hantoub Bridge, and one arriving from the west via an intersection called Police Bridge. Members of both groups post frequent updates throughout 11 January showing recognizable landmarks near and inside the city.

12 January: SAF coalition ambushes fleeing RSF, retaliates with dozens of killings and possible torture

In the early morning of 12 January, pro-SAF forces ambush convoys of fleeing RSF fighters at Police Bridge and Kariba, which is corroborated by witness testimony. Numerous videos show dead bodies, apparently combatants, in or near damaged vehicles, with signs of possible torture.

Note that combat at Police Bridge is over by 8am.

Multiple groups of pro-SAF soldiers wearing different types of uniforms arrive at Police Bridge throughout the day, celebrating and pointing at dead bodies, many of whom wear military uniforms or fatigues, though there is no sign of combat and they appear unarmed.

Most of the bodies have signs of possible torture or mutilation. The number of visible corpses increases throughout the day; one is killed on-camera.

Generals with legible name tags walk around the scene and greet the soldiers, seemingly unbothered by the dead bodies or ongoing violence.

Importantly for chronolocation, the street is crowded with hundreds of soldiers, burning vehicles, and dead bodies throughout the day. The video to the left was posted at approximately 11am.

In early afternoon, detainees are filmed in a truck leaving Police Bridge to an unknown destination. A person wearing torn civilian clothing chases after the truck and tries to climb inside, but is pulled away by laughing soldiers.

In this video, geolocated to a residential neighborhood in Madani, a group of uniformed soldiers detain a group of men in civilian clothing at gunpoint. A soldier shouts at his colleagues and encourages them to punish the detainees based on their appearance. Another group of detainees sit in the back of a pickup truck.

Based on analysis of the shadows on the ground, this video was filmed in mid-afternoon on 12 January.

Another viral video from Police Bridge, filmed in the evening, shows soldiers beating a man in civilian clothing and interrogating him about his allegiances. They shoot him until he stops moving.

13 January: Courtyard massacre

The violence at Police Bridge on 12 January takes place on the northern half of the intersection. The video above, posted 13 January, shows soldiers relaxing in the walled courtyard of a police station on the southern side of Police Bridge. Note there is no blood on the ground or on the walls. It was posted on the afternoon of 13 January, but based on the direction of shadows on the ground, filmed in mid- or late morning.

Crucially, the road is clear, so it can’t be the morning of the 12th; compare with the large crowd filling the road in the earlier video at approximately 11am on 12 January. Therefore, the video above was filmed on the morning of the 13th. There is no sign of combat or any other violence at that time.

Afterwards, a series of five videos depict dozens of dead bodies in civilian clothing in this same courtyard. We determined that they must have been filmed on the afternoon of the 13th:

14 January: bodies visible on the ground and possibly from space

A video posted at approximately 8:40 am local time shows police arriving at the checkpoint. Zooming in on the background, piles of dead bodies are partially visible in the courtyard, though the view is obscured and it appears that some bodies have been removed from the area closest to the street.

A body bag is also visible at the traffic median, and appears consistent with other body bags filmed on the 12th.

Satellite imagery taken at approximately 10am confirms the presence of irregular objects covering the ground in the courtyard where the bodies had been filmed. Unfortunately, due to limited resolution, we cannot conclusively say they can only be human bodies.

Because the dead bodies were filmed on an afternoon sometime after the morning of the 13th but before the morning of the 14th, those videos must have been filmed on the afternoon of the 13th, more than 24 hours after the end of combat in the area.

17 January – 8 February: satellite images show possible mass graves in Police Bridge and Bika

Additional satellite images taken on 17 January, 20 January, and 8 February show patches of disturbed earth and newly-dug trenches containing white objects consistent with shrouded bodies. These corroborate whistleblower testimony of burying the dead in mass graves near Police Bridge, as well as additional satellite images of fires, graves, and bodies in dried river beds in Bika and Kariba.

17 January: bodies filmed downstream in ElMielg

Also on 17 January, two videos begin to circulate, showing a group of at least nine dead bodies, some with their hands tied behind their backs, floating in a canal. The people speaking onscreen indicated that the location was somewhere in Jazira, the deceased individuals were Kanabi, and their bodies had come from the direction of Madani. This also corroborated reports from sources that they could no longer fish or drink water in the Jazira state canals because fishing nets regularly caught human bodies.

Due to the large number of canals in Jazira State, identifying the exact location where the bodies were found posed a significant challenge. Using Google Maps, we identified possible candidates with intersecting locks similar to the ones in the videos. We then collaborated with a local reporter who sent us images and videos from the ground until we found a match, confirming the location to be al-Maileg, approximately 75 km downstream from Bika.

The plan for the attacks in Jazira is said to have come from Islamists in Sudan led by Ali Karti, the leader of the Islamic Movement. This is according to a senior GIS officer who was directly involved in the attack. It is confirmed by a former senior official who is still in regular contact with the leaders of the Sudanese army.

According to two high-ranking sources, the attacks by the army and paramilitaries on the ground were coordinated by Lieutenant General Mohamad Abbas Al Labeeb, the deputy head of the GIS. Two other military sources confirm his involvement. Al Labeeb is said to have close ties with both Karti and army leader Burhan, who is believed to have been aware of the attacks.

Additional information regarding chain of command was obtained from situation reports published by war correspondents embedded with SAF on the front lines as well as social media posts by SAF officers.

Due to limited time and resources, we were unable to verify each individual piece of evidence, and some of our investigative leads regarding commanding officers and the order of battle were not ready for publication. We are happy to share our preliminary findings and raw data with researchers upon request.

The multi-risk environment in Sudan posed significant challenges for human sources on the ground, who faced surveillance and the risk of retaliation for speaking with investigators. Our investigative team, as well as third parties such as civil society organizations and humanitarian aid workers, also lacked access to many areas. This meant their publications– which might otherwise have provided important contextual and geospatial information–were limited or unavailable.

Conflict contexts can make it difficult for sources to remember dates. To address this, we relied on secondary sources, including news reports, Sudanese NGOs, ACLED, and CIR, as well as context-specific information such as known dates of SAF entrance or presence nearby. We used these sources to estimate possible date ranges of attacks, cross-reference our interviews, and fill in missing date information.

Chronolocation was also made more difficult by the unfortunate frequency of conflict events in the area: a video’s caption may accurately describe the location of the atrocity onscreen, but the event may be from an earlier phase of the conflict, with different people involved. Whenever possible, we combined different images of the same incident to triangulate information from their captions and metadata.

The relatively small number of sources willing and able to testify to international journalists means our data is likely not comprehensive. There may be additional kambo attacks not recorded in our database, or visual evidence that we could not connect to a specific kambo without witness testimony. The challenging media environment in Sudan further constrained our verification efforts.

Investigating rural Sudan is particularly challenging due to the lack of reliable geospatial data. Mapping services like Google Maps, Wikimapia, Mapillary, and OpenStreetMap provide limited coverage, and limited demand means that high-definition satellite imagery recorded during the relevant time frame is scarce. For many locations, few publicly available reference images exist. The most recent UN OCHA Sudan settlement survey is the most comprehensive data we could find, but the survey was conducted in 2020, does not contain all villages, and in some cases assigns different names than our sources do. While Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team’s data is more recent, few of their indicated settlements have names at all.

Adding to the difficulty, transliteration of Arabic is inconsistent: Google Maps mostly uses Arabic names while OCHA uses English transliterations. Some villages have multiple names (e.g., official, former, and local nicknames) while some names apply to multiple villages.

In a few cases, a village was referenced in interviews only by the name of the adjacent town, or the village referred to was actually a region containing a collection of villages. In other cases, a location was occupied by RSF and then attacked by SAF, or actual collaborators were arrested alongside civilians accused of collaboration. We included notes about these nuances in each attack’s description. While villages could have been attacked and occupied at various points throughout the course of the war, we only included them in our verified kambo attack dataset when we had three sources who could attest to an attack by SAF or SAF-aligned forces.

When in doubt about a village being part of a larger village complex, we logged only the larger village complex to avoid duplication. Thus, our numbers could represent an undercount.

In some instances, we were able to send local reporters to locations to verify attacks or collect additional information. However, due to the security situation, we had to exercise caution to avoid risking people’s lives.

Social media is of course socially mediated, which introduces several challenges:

Fog of war: parties to the conflict use social media as propaganda (disinformation), while social media users and influencers exaggerate or create misunderstandings (misinformation). An example of disinformation is when a video of civilians allegedly killed by SAF in Jazira was reposted with a new caption claiming they were killed by RSF in al-Fasher. Misinformation, on the other hand, could describe the spread of rumors.

Deletion of social media evidence and use of private chats by combatants limits publicly available evidence. This effect is distributed unevenly–tech-savvy combatants are both more likely to post and more likely to take steps to protect privacy, such as automatically deleting posts or using private chats.

Areas with less data connectivity produce less evidence posted online, which does not necessarily mean they experienced less violence.

Content moderation and deletion of evidence by platforms skews available data; for example, visual evidence on X or TikTok gets deleted faster than on Telegram or WhatsApp. Open source data is further skewed by the relative technical difficulty of collection on different platforms. WhatsApp, for instance, has not been investigated as thoroughly as Facebook or Telegram due to difficulties in searching WhatsApp. Due to resource constraints, we were only able to verify a subset of our database, which also introduces potential bias.

Our methodology acknowledges several types of uncertainty:

We articulated date confidence levels using qualifiers such as “likely” or “unclear” in the date category. Uncertainty was systematically logged. Villages that were attacked but for which we lacked verified information were recorded in a separate sheet with sources and comments as unverified but potentially valuable lead evidence.

Ethical constraints limited our work in certain situations. There were potential dangers to reporters in the field when accessing high-risk zones like mass graves still under strong military presence.