Fate of Ukraine’s Foreign Students

Tracing non-white students who fled invasion but faced Europe’s hostility

The EU’s decision to offer unprecedented rights and freedoms to refugees fleeing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine less than a month after the war began was widely celebrated. What was not said at the time was that the policy was drawn up to intentionally exclude a considerable number of non-European refugees fleeing the war.

This double standard was not an accident. The first draft of the legislation implementing the Temporary Protection Directive (TPD), a measure designed to provide protection for at least one year, contained a clause stating that all foreigners residing in Ukraine on a long-term basis – regardless of their country of origin – would be granted the same rights as Ukrainians. When the text came out of the EU council meeting this clause was gone.

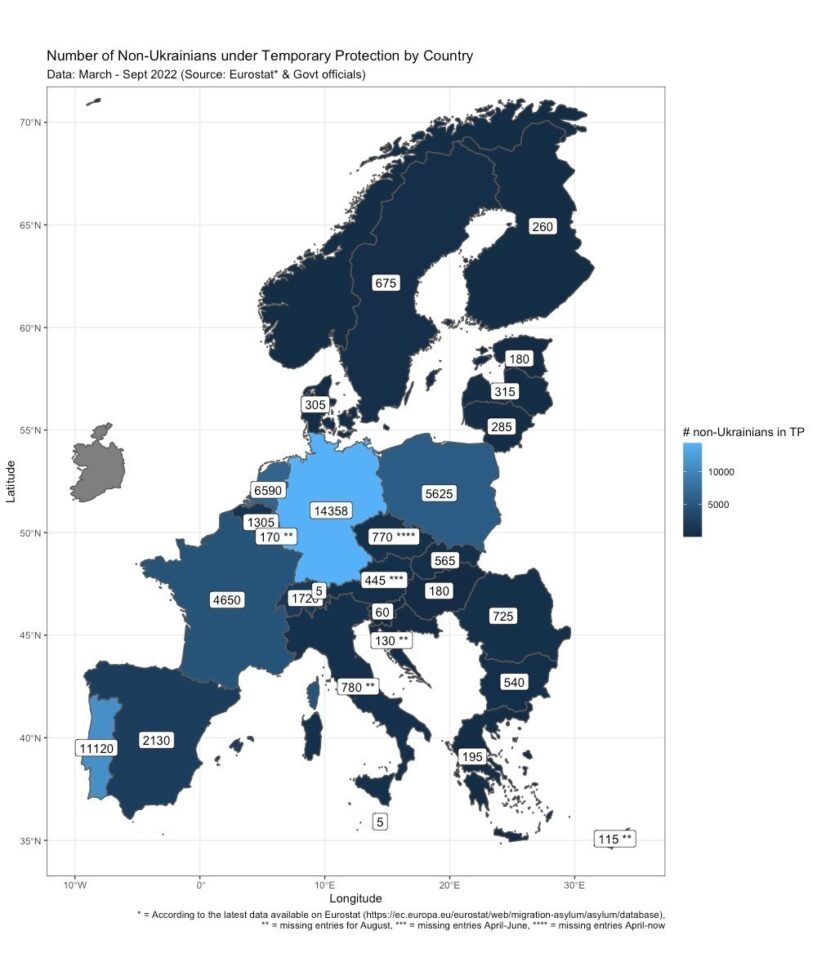

This decision has had very direct consequences on the lives of many of the nearly half a million third-country nationals who were living in Ukraine before the war. The data we collected reveals that only 54,443 of these people were offered temporary protection in the EU. While some 5 million Ukrainians got refuge and rights, many non-Ukrainians were given time limits on how long they could stay, while others were refused any form of protection, rendering them undocumented.

The tens of thousands of African and South Asian students enrolled in Ukrainian universities on student visas fell outside the scope of the TPD. We spoke to more than 30 students who spent months applying to European universities, only to be told they do not meet visa conditions and language requirements. Some, already traumatised during the invasion, found themselves homeless, while others are facing imminent deportation. While native Ukrainians were met with open arms, many of their non-white classmates met with discrimination and xenophobia.

METHODS

In tandem with diaspora groups, activists and lawyers, we spent the past eight months following students who fled Ukraine. Through phone calls, voice-notes and text messages, people shared updates of their attempts to settle in EU countries as they struggled to navigate visa bureaucracies and access accommodation. Students shared email exchanges with European universities and rejection letters from the same institutions that accepted several of their Ukrainian peers.

We obtained internal documents written by German diplomats on 4 March ahead of the implementation of the TPD revealing that Poland, Austria and Slovakia were among the countries that objected to including third-country nationals in the directive.

Our partner publications reached out to their individual governments and university authorities to find out what protection measures had been implemented for third-country nationals. This revealed that a myriad of often contradictory rules were being applied. A non-bureaucratic solution was found for Ukrainians, while pragmatic reception and recognition for non-Ukrainians was denied.

We analysed and collected available data from the European Commission, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and national governments, revealing that – despite 325,000 third-country nationals fleeing Ukraine to neighbouring countries since the onset of the war, only 54,443 of them were offered temporary protection in Europe. Of those, we found that nearly a quarter were granted TPD in Portugal, the only country to give the same rights to non-Ukrainians, including international students who were in Ukraine on short-term (one year) visas.

STORYLINES

According to NIDO, the Nigerians in diaspora organisation, many international students who fled Ukraine have found themselves homeless, while others are facing imminent removal. Many have been stripped of the rights they previously had in Europe and can no longer access higher education. “We receive dozens of calls from desperate students every day asking for help with accommodation and food, as well as from depressed parents who spent all their money on their children’s tuition in Ukraine. It is so bad that some have told us they were considering suicide”, says Chibuzor Onwugbonu, a volunteer at NIDO.

In Germany, rights granted to third-country nationals fleeing the conflict vary between federal states. While some cities granted six-month non renewable visas to international students who could prove they were enrolled in Ukrainian universities, others failed to put in place adequate permits. In one instance, a student moved between six different cities and spent months struggling to find accommodation before she ended up sleeping for weeks in Berlin Central train station.

In the Netherlands, immigration authorities announced that from 19 July onwards they would stop processing applications from non-Ukrainians with safe countries to return to and that those who had obtained the status would not be allowed to apply for renewal. The Dutch government has described the act of these individuals applying to stay in the country after fleeing Ukraine as an “abuse” of the system.

In France, only 200 international students have been accepted into university. The requirements for entry include demands for a bank account with at least €3,750 and proof that accommodation has been secured (or €7,500 for those who are yet to find housing). These are the regular requirements for international students in France, but they have been waived for Ukrainian students fleeing the war. At least 10 non-Ukrainian students received “obligations to leave the French territory”, a letter threatening them with deportation.

Dutch MEP Thijs Reuten told us that omitting international students from the protection directive was not an oversight, but a decision aimed at excluding non-Europeans, suggesting an element of racism: “It seems almost certain to me that the countries of origin of the international students played a role”. Cornelia Ernst, German MEP, said the restriction was “solely a political decision”, which was “strongly criticised at the time”, adding: “In practice, this led to first- and second-class protection seekers fleeing Ukraine – an unacceptable discrimination.”

We also reported on the difficulties facing third-country nationals attempting to join their families in the UK. Deborah, a 19-year old Nigerian medical student who was studying in Kharkiv, has spent months trying to join her parents and siblings in the North of England. Despite fleeing war, and her family being settled in the UK, the British government’s scheme for people fleeing the Russian invasion does not accept applicants who are not Ukrainian or related to a Ukrainian national. UK government data shows that even those who are related to Ukrainians – indicating that they should be eligible – have a far higher refusal rate under the scheme than Ukrainian nationals, at 14 per cent compared with 0.4 per cent.

To keep up to date with Lighthouse investigations sign up for our monthly newsletter

The Impact

Our investigations don’t end when we publish a story with media partners. Reaching big public audiences is an important step but these investigations have an after life which we both track and take part in. Our work can lead to swift results from court cases to resignations, it can also have a slow-burn impact from public campaigns to political debates or community actions. Where appropriate we want to be part of the conversations that investigative journalism contributes to and to make a difference on the topics we cover. Check back here in the coming months for an update on how this work is having an impact.