Surveillance Secrets

In the spring of 2024, Lighthouse found a vast archive of data on the deep web. It contained thousands of phone numbers and hundreds of thousands of locations from nearly every country in the world.

The data came from a little-known surveillance company called First Wap. Headquartered in Jakarta but run by a group of European executives, First Wap has quietly built a phone tracking empire spanning the globe.

There have been leaks of telecom network targeting data in the past (some of which Lighthouse has written about). But none of them has included this amount of successful targeting of individual phone numbers.

The archive was a starting point for Surveillance Secrets, a collaboration between Lighthouse Reports, paper trail media and 12 other partners that lifts the lid on First Wap’s activities. The team found material inside the archive for dozens of stories, including how the company’s tracking tech was used against Rwandan dissidents targeted in an assassination campaign, a journalist investigating corruption in the Vatican, and a businessman being investigated for compromising material.

Getting to those stories took months of analyzing 1.5 million rows of obscure telecom data. Unlike top-tier spyware firms, such as the notorious NSO Group, phone-tracking firms like First Wap have flown under the radar. Standard tools used in spyware investigations — such as device forensics — were unavailable to us; there was no blueprint examining a firm such as First Wap. In this technical explainer, we explain how we approached the data to understand the company’s operations.

We sometimes think of the surveillance industry as a pyramid. At the top are the elite spyware companies, selling expensive, highly targeted and invasive tools like NSO Group’s Pegasus or Intellexa’s Predator. At the bottom sit the preliminary tools that help enable surveillance operations: OSINT and social media scraping tools to develop profiles of targets, internet infrastructure to spin out lists of honeypot domains, and vulnerability vendors trading identified weaknesses in operating systems and other software. Sandwiched in between is a middle layer — firms that track locations or intercept communications at scale, like First Wap.

With the top of the pyramid grabbing the most attention, the middle tier has managed to operate with less scrutiny, despite enabling surveillance on a far broader scale. Lighthouse has made a point of investigating actors in this middle tier. It’s that focus that brought us to First Wap, a little known phone-tracking firm headquartered in Jakarta.

First Wap’s primary product is a surveillance tool called Altamides, an acronym for “Advanced Location Tracking and Deception System.” While Altamides boasts a number of capabilities, its flagship feature is the ability to track a phone number anywhere in the world without leaving a trace on the device. Besides location tracking, Altamides also has the ability to intercept text messages and phone calls, spoof messages and even breach encrypted messaging apps like WhatsApp.

The investigation started with a 1.5 million row archive of surveillance operations carried out via First Wap’s systems. Within the dozens of columns we found a relatively straightforward taxonomy of data – times and dates, latitude and longitude, phone numbers, country and phone operator names, map URLs – alongside fields that were at first glance less obvious, such as query methods, cell identifiers and other technical details. Numerous internal references in the dataset demonstrated its ties to First Wap and the Altamides tool.

What was clear was that this was a record of years of location tracking, targeting thousands of phone numbers in a vast range of countries. What was less clear, at first, was how to make sense of this mass of data.

On any given day the dataset might exhibit activity in dozens of places. On initial analysis, we saw that the majority of targets were tracked a small number of times, while a minority were tracked heavily or regularly. Similarly, while nearly every country in the world featured in the dataset, certain regions emerged as clear hotspots, either in terms of total volume of tracking, or in terms of number of devices tracked.

We wanted to understand who was being targeted. So we ran all of the more than 14,000 numbers through a combination of OSINT tools which link phone numbers to internet accounts (including OSINT Industries, Social Links Pro, PIPL, ESPY and Effect Group). We mapped the links between numbers and people using Maltego, and then connected this to the diachronic tracking data with an interactive user interface developed by team member Christo Buschek.

Although this automated process surfaced thousands of potential matches between phone numbers and names, we only considered identifications to be valid if more than one datapoint connected the number to a person (beyond simply a matching name). A team of more than ten reporters at Lighthouse and paper train media spent months building up a list of high-confidence targeted individuals, which ultimately at time of publication included over 1,500 phone numbers.

Looking for outliers in the dataset led us to cases of harm and obvious misuse. Among the most heavily featured numbers we came across Anne Wojcicki, co-founder of 23andMe and at the time married to Google’s Sergey Brin, who was tracked more than 1,000 times as she moved across the San Francisco Bay Area. We also detected cases where tracking was automated, with timestamps at the same minute of each hour, as was the case for Gianluigi Nuzzi, a well known Italian journalist who had uncovered a corruption scandal inside the Vatican.

While we could see who was being tracked, we could not see which Altamides user was carrying out the tracking. Understanding the broader patterns of surveillance, and ultimately their motivation, required searching for “clusters” of targets — networks of people whose tracking was connected in time or space. A series of Nigerian election officials, for example, were all tracked in the city of Bauchi ahead of Nigeria’s 2011 election. In 2012, meanwhile, the wife of General Faustin Kayumba and the bodyguard of Patrick Karegeya, two founders of the Rwanda National Congress — an opposition movement operating in exile in South Africa — were tracked within minutes of one another. Both men had been targeted for assasination, with Karegeya found strangled in a Johannesburg hotel room 18 months after his bodyguard was targeted by Altamides.

As we continued to identify phone numbers, we homed in on a portion of the dataset that indicated use in customer demonstrations. This data showed how First Wap’s executives, or middlemen they had contracted to market their technology, tracked themselves and their associates so that potential clients could experience Altamides in action. In turn, these records allowed us to see the movements of First Wap’s salesmen as they hopscotched the globe, interacting with potential customers – who themselves were sometimes exposed in the data, either by identity or location.

So how did First Wap connect the numbers in the dataset to locations? And why did some of the data contain blank locations or unsuccessful location attempts?

In contrast to top-tier spyware like Pegasus, First Wap’s Altamides can’t infect a phone, but operates entirely at the level of the telecom network. First Wap’s late founder, Josef Fuchs, realized before almost anyone that by exploiting an antiquated communication system he could trick phone networks into revealing the locations of their users.

Signalling System 7, or SS7, is a decades-old set of protocols that allows phone networks to communicate with one another, routing messages and calls across borders. It was never designed with security in mind, and while operators have moved to more secure evolutions with 4G and 5G, they still need to maintain backwards compatibility with SS7. This is likely to remain the case for years if not decades to come.

Phone networks need to know where users are in order to route text messages and phone calls. Operators exchange signalling messages to request, and respond with, user location information. The existence of these signalling messages is not in itself a vulnerability. The issue is rather that networks process commands, such as location requests, from other networks, without being able to verify who is actually sending them and for what purpose.

These signalling messages are never seen on a user’s phone. They are sent and received by “Global Titles” (GTs), phone numbers that represent nodes in a network but are not assigned to subscribers. Surveillance companies have often leased GTs from phone operators and used them to send unauthorised signalling messages into other networks, benefitting from the fact that the signalling messages appear to be coming from the legitimate operator which owns the GT.

First Wap primarily works via in-country installations of Altamides. In this setup, a government client uses Altamides via an SS7 link belonging to a local phone operator. The local phone operator provides the GTs and Altamides uses these GTs to conduct location tracking domestically and internationally.

But the company also offered customers SS7 connectivity through Liechtenstein’s national operator, Telecom Liechtenstein (formerly Mobilkom). The First Wap archive shows Altamides using GTs from Mobilkom to carry out hundreds of thousands of location tracking queries.

The dataset we obtained does not contain the raw signalling messages (unlike our previous exposé of 2FA code routing), but rather a record of the tracking queries and their results, along with additional technical information added by First Wap. Here is an abridged record for a phone belonging to Gianluigi Nuzzi, the Italian journalist tracked while investigating corruption at the Vatican.

Comparing the originating Global Title extracted from the data with historic records of phone operator connectivity, we can see that the tracking query targeting Nuzzi’s phone was sent via Mobilkom Liechtenstein.

In the method field, you can see the type of SS7 command First Wap used to request a location. Two commands occur regularly in the dataset: PSI, which stands for “Provide Subscriber Info” (used in the example above) and ATI, which stands for “Any Time Interrogation”. Both these commands have regularly been abused by location tracking firms. Security experts recommend that operators perform strong validation before processing PSI commands while GSMA, the trade organization for mobile phone operators, recommends that ATI commands only be sent within the same network and not between networks on account of the high risks of abuse associated with this command. The First Wap archive includes nearly 600,000 ATI commands.

In Nuzzi’s case exemplified above, his operator did process the PSI request, and his location was successfully returned. This took the form of a string of digits, called a “Cell ID” (see next section).

Over time, more phone operators have started to install firewalls to counter this type of threat. But maintaining them is complicated, and spotting this type of location tracking request within the millions of legitimate queries sent to an operator’s subscribers on a daily basis is challenging. The more legitimate the source, the more likely it is that the operator on the receiving end of the query will let it through. Examination of the dataset shows that a considerable proportion of the activity in it was sent via Mobilkom Liechtenstein, which has excellent world wide links to other networks and, operating in the heart of Europe, also appears to be a trustworthy traffic source.

In response to this investigation, Telecom Liechtenstein (formerly Mobilkom Liechtenstein) said it was unaware of any misuse of its network by First Wap. The phone operator said it had immediately “suspended its business relationship with First Wap” and that “If the allegations are substantiated, the collaboration will be terminated without notice, and the company reserves the right to take legal action.”

First Wap stated in response to this investigation that it has “fully complied with the statutory and legal requirements and have also imposed this on our business partners”. The company stated that it has “never attempted to hack an SS7 stack or similar” and has “not offered or sold our products and solutions to repressive systems or sanctioned countries or individuals.”

Commands such as ATI and PSI do not themselves return longitude and latitude coordinates. Instead, they return a Cell ID, which is a unique number assigned to a cell in a mobile network and physically designating a tower or base station. A complete ID is made up of four parts: the country (MCC), network (MNC), area (LAC) and finally the cell.

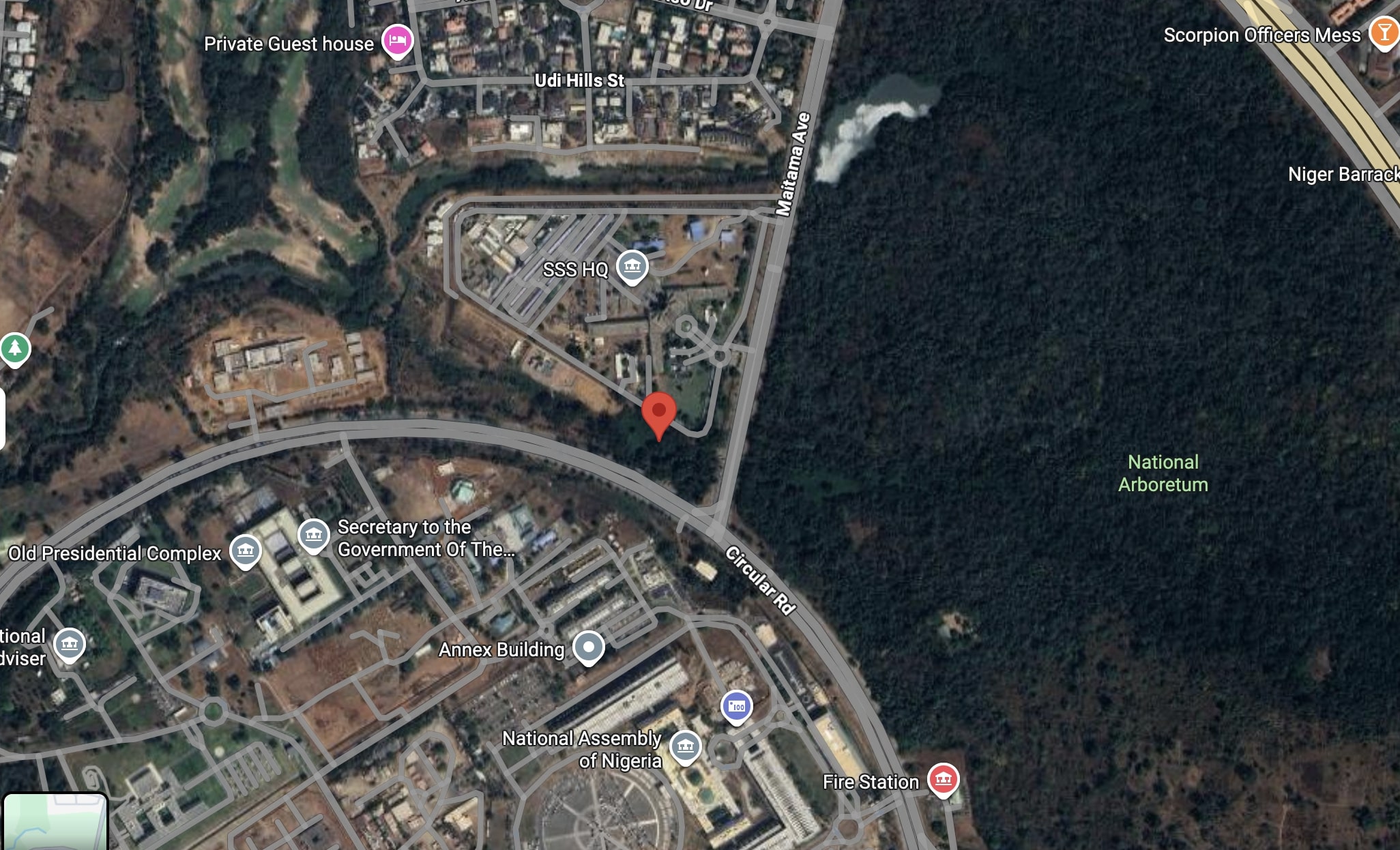

Below is a tracking record for a First Wap sales representative during a 2011 trip to Nigeria.

Cell IDs can be mapped to a longitude and latitude using proprietary or public databases. Governments and operators will maintain their own lists, while there are also publicly available crowd sourced databases such as OpenCelliD. When First Wap installed a system in a country, it requested the client to provide an up-to-date mapping of its domestic cell towers so that Altamides could convert Cell IDs to locations. But, as a brochure we obtained demonstrates, the company also offered to facilitate foreign Cell ID mapping for its customers, thus allowing them to carry out tracking operations abroad.

In the case of the First Wap sales representative cited above, the Cell ID was successfully mapped, and the phone was tracked right next to the headquarters of Nigeria’s State Security Service (SSS) in Abuja.

The accuracy of such mapping depends on the density of cell towers in an area. In urban areas, such as Union Square in San Francisco, the high density of towers means that individual Cell IDs can be quite precisely located. In rural areas, there might be only one tower servicing a much larger area. So the accuracy of the map data depends on real-world physical context as well as technical issues of signalling queries.

Across the span of the archive, it is clear that First Wap’s database of Cell IDs was still evolving. This meant that in many cases Altamides successfully obtained a Cell ID but was unable to map it into longitude and latitude. In these instances, the tool would either provide no coordinates, or would provide an estimated centre of a much larger area.

Most countries have a legal mandate to carry out domestic phone network surveillance. The First Wap archive demonstrates, however, how phone network connections can be leveraged to allow tracking all over the world, without authorisation from the targeted networks.

In recent years, a number of investigations have explored the ways in which surveillance companies gain access to phone networks to enable this type of tracking. Lighthouse and its partners have previously written about how SS7 abuses were linked to the murder of a reporter in Mexico and a crackdown on an activist in Congo, and how they were enabled via leasing of Global Titles.

Although in recent years some phone operators have acted to improve security, global imbalances remain. Stopping unauthorised signalling is expensive and as such tends to be better implemented by wealthier operators. When operators in the global minority world allow surveillance companies to access their systems and send traffic, they are increasing risk to people in the global majority.

Last year, the UK’s telecom regulator took the step of banning Global Title leasing on the grounds that phone operators had failed to manage risk and UK networks were carrying large amounts of malicious signalling traffic, including surveillance traffic, into networks worldwide. But for real change to occur, other regulators in the EU need to follow suit.

Cover image: Erik Carter / Illustration of Earth in space with red map pin icons forming the shapes of the continents on a blue and green globe.